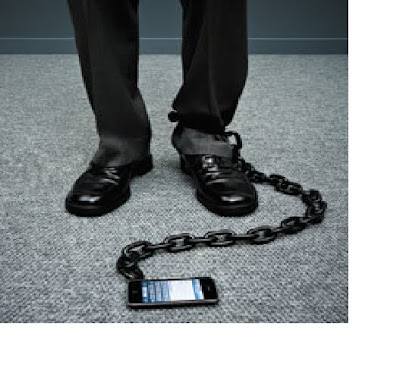

Information, the very thing that makes it possible to be an engineer, a doctor, a lawyer, or any other kind of modern information worker, is threatening our ability to do our work. How's that for irony?

The global economy may run on countless streams, waves, and pools of information, but unrestrained, that tidal wave of data is drowning us. It washes away our productivity and creativity, swamps our social lives, and can even shipwreck our relationships.

Some of us actually call it "quality time" when we sit on the sofa with our kids scrolling through e-mail on our BlackBerries. Take a few days of well-earned vacation and you spend them dreading the thousand e-mails that await your return—e-mails you'll spend a day clearing while putting off real work. On your next trip, you try to head off that problem by taking your computer along so you can chip away at the inflow late at night in your hotel room. The result? Thoughts of work cloud your enjoyment of what should be a respite from office life.

But information overload isn't just about having too much e-mail, voice mail, and text messages. It's a much more complex problem, and its effects take a toll on companies' bottom lines and on their employees' well-being. The time that information workers invest in coping with this overload is significant; at Intel, where I was until recently a principal engineer, we assessed the loss due to unnecessary e-mails and unproductive interruptions at 8 hours a week. In a 1996 Reuters survey of 1300 managers worldwide, two out of three respondents associated information overload with loss of job satisfaction and tension with colleagues, and 42 percent attributed ill health to this stress. Today, more than 10 years later, the numbers would likely be even higher.

Academic researchers have been studying the problem for years, and now at last organizations are beginning to wake up and take action to mitigate it. Some are deploying training and behavioral change programs, trying their hands at setting up quotas and encouraging alternatives to e-mail, and experimenting with interruption-free "quiet time" blocks. Change is in the air.

Whatever you want to call it—infomania? infoglut?—it's a combination of two elements: queued messaging overload and interruptions or distractions. Queued messaging overload can happen anywhere you have a queue of incoming messages, most notably your e-mail in-box. Some of the messages are critical, most are not, but they all accumulate until you deal with them. Information workers typically receive 50 to 200 work-related e-mails daily. Surveys at Intel showed that people spend some 20 hours a week processing work-related e-mail messages, of which about a third are unnecessary. Processing this third took workers about 2 hours a week.

Interruptions and distractions take many forms. They include ringing phones, text messages, instant messages, the chime that alerts you to incoming e-mail, and, of course, a colleague dropping by your office to chat. Any of these will break your chain of thought and may make you drop your current task to start another. The myth that this is okay because people can multitask is just that; ample research proves that the brain simply doesn't work that way.

Even when the interrupting task is related to work, you still waste time as your brain switches from one task to another and back again. Field research by Gloria Mark and her colleagues at the University of California, Irvine, shows that information workers are interrupted on average every 3 minutes. Even if it takes the brain only a minute to get back in gear, that's a lot of wasted time.

Constant distractions also make us stupid. Research clearly demonstrates that interruptions degrade accuracy, judgment, creativity, and effective management. The psychiatrist Edward Hallowell coined the term attention deficit trait to describe this phenomenon and found that it makes people perform far below their full potential.

Creative thinking, essential to many engineering jobs, requires long stretches of uninterrupted time. Programmers are known for working odd hours, when they can have the quiet they need to concentrate. Other professionals find that their best thinking takes place on airplanes and in hotels during business trips, when they're somewhat disconnected. But even this time is shrinking fast as remote access becomes ubiquitous. At one company, researchers found that recipients read 70 percent of e-mails within 6 seconds of arrival. In the battle between creative thought and distractions, creativity is losing.

No comments:

Post a Comment